Chapter 15: The Whole Story

The Reading

“What is it that makes facing mistakes, weaknesses, or regrets so terrible that they must be completely and utterly denied?”

The author highlights how we create stories from a single perspective, which comes from, reinforces, and becomes our baseline for judging things that relate to it. She gives the example of believing that her husband was “not raised as well as she was” because he didn’t do things the way she expected and defined as “right.” Rather than making the all-too-obvious connection with how this informs our judgement of people and groups of people (that we like to think is based in their race), she connects this to our understanding of American history as a whole, ultimately asking:

“How [do we change ]the dominant narrative…so that American history becomes a collection of short stories, as opposed to an epic told by a single author?”

The Study Question

Think of a historical event in American history, perhaps the signing of the Declaration of Independence, the arrival of the Statue of Liberty, or any one of the wars Americans have fought. Where have you learned what you know about this event? Whose perspective did you learn? If you went in search of a fuller story, whose viewpoint would you seek?

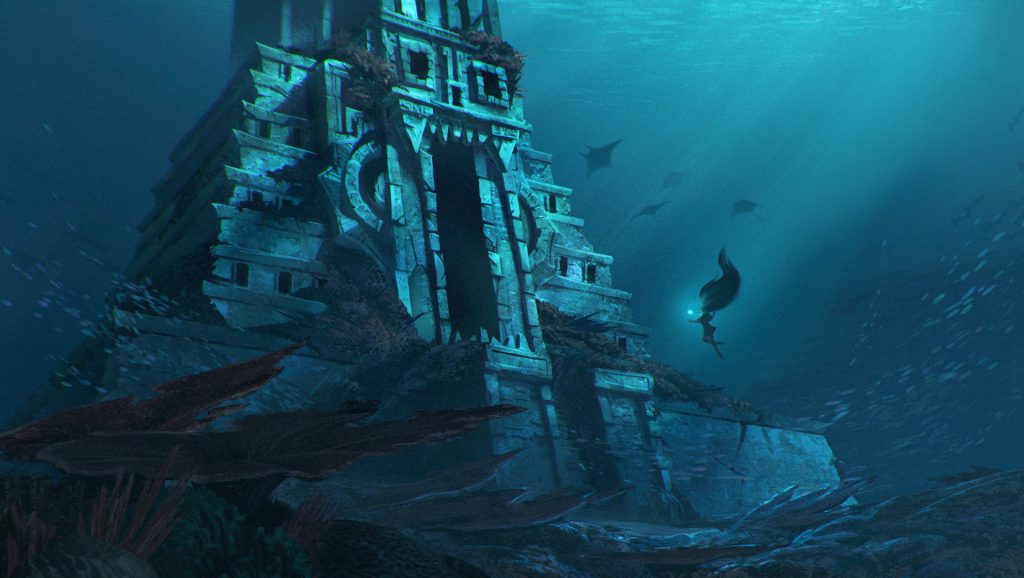

Gosh, just one? I’d like to go to England and ask the Puritans’ neighbors what that situation looked like to them before the Puritans decided they were being persecuted and took off across the sea. To South America and ask the Mayas what how many people were in their nation in 1450, and then 1495, to understand whether these ‘mighty’ Europeans really had that much advantage, even with their weapons and technology – or if a population decimated by early explorers’ germs was simply insufficiently recover to kick their butts. The people who signed treaty after successive treaty, to ask if they really believed this would be the contract the Americans finally kept, or if they simply figured that not signing would get them wiped out, so it was better to let their world be killed slowly, on the hope that they might take it back in future.

Yikes! That’s pretty bleak. The victors do write history, though, and on favorable terms. I would also be curious about the neighbors, whether they were as glad to see the Pilgrims/Puritans go as much as the P/P were. Sometimes it sounds like the P/P were just unhappy with life and thought moving away would solve their problems. But the early years in America under the rules of Puritans and Pilgrims were not always happy ones, either. And the Salem Witch Trials were not instigated by the moderates and the placaters.

I’ve been thinking about this post for a while now, about the Pilgrims/Puritans and their desires to make a new home for themselves, a purer land, a place for the people who really “get it” about being right and good–and about how they rejected all the others as impure. I’m reading a book about this time in history (it’s about more than this, but the section I’m in is covering the landings and the creation of the colonies

It’s a complicated story, as most stories about history are, and the simplified version we get of holy brethren seeking a place to worship god as they pleased is perhaps eliding some of the facts. The colonists weren’t seeking freedom for everyone as much as they were seeking a place for themselves to be in charge of who was approved. The journeys and the colonies weren’t for their benefit, but for the benefit of the companies that sponsored them. And the companies that sponsored them were engaged in business transactions that would end up planting white supremacy in the Americas. One story (which I haven’t yet verified) is that the Mayflower itself was used for transport of both free whites and enslaved Africans (although not the famous journey that ended up depositing Pilgrims at Plymouth Rock).

The story here (for me) isn’t so much that “there are things we were never told!” but more that we were told a carefully scrubbed version of history to make our founding sound like a hardscrabble attempt to found a new land for free worship. The background of business conglomerates using whatever they could for profit is there, if you look at the public texts, and the background of a-moral transactions is there as well. We don’t tie in the colonists directly with white supremacy even though the idea that you could leave a country where you must co-exist with neighbors not of your liking and just go to another land and just take land and build houses and farms among people who are already there is, of course, the height of white supremacy–we can just declare it as “our” land and “our” home, much as the declaration of it is “our” god isn’t about our loyalty to that god but that we own that god & can determine who can access that god.

We are, indeed, told the “scrubbed” version – and yet, the seeds of truth remain.

The Mayflower as a slaver story appears to be a myth based in misidentification. The Pilgrims’ Mayflower was…a bit long in tooth…when they sailed. After that voyage, it went to running French wine, but not for long. It was decommissioned and sold for scrap only a few years later. A different vessel, also named Mayflower, did indeed carry Africans to the Caribe

You make a pretty tidy and compelling presentation of the attitude here: I’ts ours because we say its ours – land, home, god – and we will determine who gets to b a part of “us.” At the time, white colonists were the minority – so the modern excuse of ‘majority rule” can hardly be applied. That leaves very little other than hubris as a basis for their actions.