The year after I was born, during the Viet Nam war, my dad went away. He didn’t speak of this time much – a few carefully selected stories – but he did something that, for the time, was pretty uncommon. He bought a Super 8 movie camera, and he brought home movies

He had few photos from that trip. But he brought back what might be the last video taken of USS Pueblo before she was captured, and pictures of a place in Hong Kong that he found beautiful (or maybe just exotically “different”), and fascinating for its history.

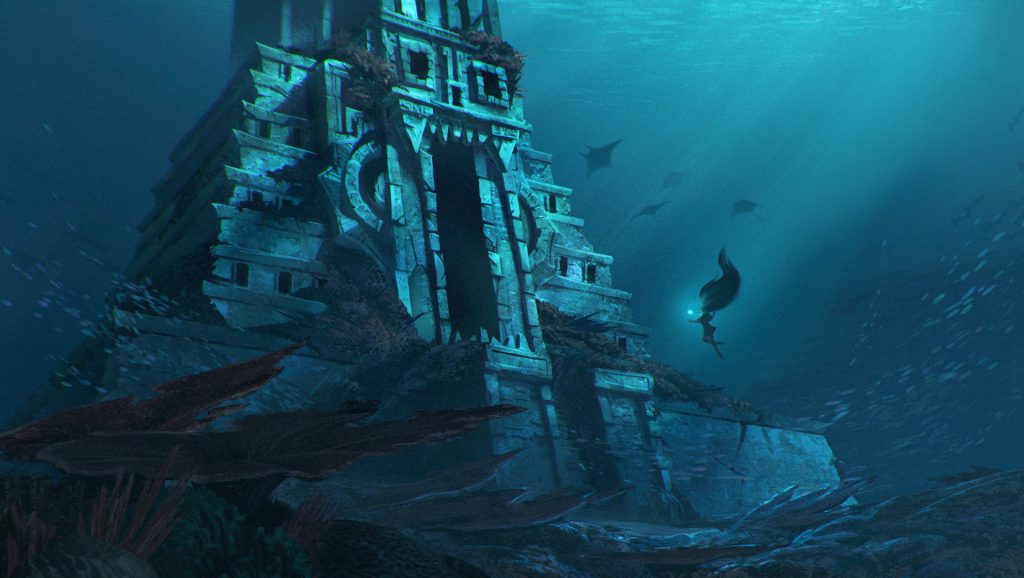

This beautiful garden had been created and then maintained by generations of the same family, each new caretaker adding his own mark, or the mark of his era, so that the garden formed a sort of history of the men who had tended it and the times in which they had lived.

This kind of history and continuity was fascinating to my dad. His own family had been more scattered; his father was a bit of a wanderer, and my dad’s dream was to build something more stable and continuous. His several-greats grandfather had been an Irish potato famine refugee. Patrick O’Moore, the family said, had landed somewhere on the East coast, married an eastern Cherokee woman, then moved West sometime after the “Trail of Tears” to be with her family members there. They lived in Grove, OK, in the Cherokee area of the Indian Territories, until someone (maybe my dad’s grandfather, but possibly a generation earlier) moved to Lawton, where most of the family remained.

Something about his transient early life made my dad crave the kind of continuity reflected in that ancient Chinese garden. In the 1980s – 20 years after his trip to Hong Kong – he bought land and built a house from the ground up, with the idea that it would be a ‘homestead’ for our family, something that could be passed on to his grandchildren and be a point of history and stability to them.

It’s a beautiful, peaceful place set in 10 acres of land on a quiet point, where the deer and the elk walk up from the saltwater flats to drink from a natural spring. When dad died about a year and a half ago, he did so knowing that he had created a special thing, and made the dream of his life into a reality.

In the past few months, I’ve discovered that neither of the stories above – about the gardens or Dad’s family – was true.

Dad would have been fascinated, and at first I thought it was sad that he didn’t live to examine my new discoveries with me, but I think maybe it’s good that he didn’t. Those truths would have changed his understanding of things he believed and built, and that might have been too great a loss.

The garden was called Tiger Balm Gardens, and it was a very unusual place.

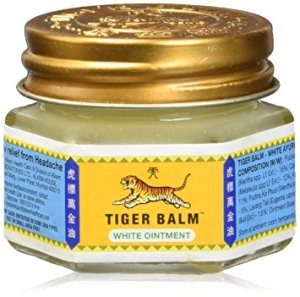

Profits from Tiger Balm, still sold today, financed the creation of the Tiger Balm gardens

A wealthy Chinese businessman created the gardens in the 1930s as a sort of tribute/introduction to Chinese culture for western visitors. In fact, he created three: one at each of his extended family’s homes in Hong Kong, Fujian, and Singapore. It’s unusual for the gardens of such a house to be open to the public; in addition to tourists, many locals in Hong Kong visited regularly to enjoy the beautiful site.

The tour guides’ patter was meticulous, and I am confident that Dad wasn’t the only young sailor who failed to realize that he wasn’t looking at a centuries-old family garden, but a 30-year-old theme park.

That’s not a bad thing, I think. The legend of Tiger Balm Gardens is greater than its reality. It’s a story of the kind of family continuity that Dad craved, but also an opening to understand the history of a people and a region which was very different from his own. It offered many westerners a glimpse into a people and a way of thinking that they might otherwise not have seen, and it undoubtedly influenced many to learn more.

While the story of Tiger Balm Gardens is not “factual,” its legend holds truths which carry greater weight. Or, I should say, “held” – the garden my father saw was destroyed in 2004 to make way for a housing development.

I am glad to know the facts – and sorry that I will never know its truths first hand.

The other story – the history of dad’s family – was a little tougher to unearth. My grandfather was born in the Indian Territories, a few years before that area became the state of Oklahoma. Record keeping was not always similar to the rest of the United States, and a lot of archives are not yet online, so being on the west coast made it a challenge to find anything helpful. When I did find records, they were often confusing or mismatched. “Using nicknames rather than real names” seemed to be a family tradition..

My grandfather was named Washington Lafayette Moore. But his family called him “Fate” (“’Cuz he was lucky,” Dad explained). I have never found a record of any type that lists his full name – even the census records from when he was a toddler list him as “Fate.” I did finally get hold of his social security app, which lists his name as “Fate L. Moore.”

His father is listed, alternately, as Robert W and Wat Robert (“Watson” was my father’s middle name, and seems to have been handed down). Fate’s mother seems to have been called Jean – but according to that SS app, her name was Ida. Or Martha Ida… Martha is also Wat’s sister’s name. Dad’s notes on the back of family photos say Fate’s mom was called “Star.”

Even when I could find the names in records, they could be a maze unto themselves.

That Cherokee ancestor – whose name might have been Luna or Lura – does not appear on the Dawes rolls, but that wasn’t uncommon. Dad explained to me that white men married to native women often encouraged them not to register. After all, if you weren’t legally an Indian, and you were married to a white man, that more or less made you legally white, right? And as our nation rolled into native “relocations” and civil war, being able to legally erase your not-whiteness could be beneficial. (In reality, research would teach me that ducking the Dawes Commission wasn’t actually an easy thing to do, at least in some areas. This seems to be more of an excuse used by people who can’t find a documented connection.)

So, there are all kinds of reasons that this story was hard to dig up or verify. As it turns out, the primary reason it was so challenging might be because it wasn’t true.

Each year, more records become available online, and I periodically go back to check. This year, new records and some genealogical work done by others netted a treasure trove!

The reason I could never find the point where the family moved from Grove to Lawton is because it never happened. (Wat) Robert went to that part of Oklahoma directly from his birthplace – in Arkansas.

Well, OK. Grove was near the state line, and the Old Settlers (Cherokee who moved west before the Trail of Tears, as Lura’s were supposed to have) settled there. Those boundaries were still evolving in that time period, and someone got it wrong.

Looking at the records in Arkansas, I found Robert’s mother, Clara living with her own parents and two children but no husband. (Robert was born in the early 1860s – a lot of husbands didn’t come home during the Civil War.)

A tiny trove of records revealed that Clara received assistance from the Freedmen’s bureau – an organization briefly set up to help freed slaves and poor whites who were devastated by the collapse of the plantation economy. Was Wat’s mom black? Is that what all the confusion was about? Cherokee freedmen…?

The Bureau records declared Clarinda “Clara” Reed to be white. The census record shows there was a second family living on her father’s farm – laborers, who are identified as black – but they had a different last name and are clearly listed as a distinct family, separate from the Reeds.

Robert’s dad was white too. Although I only found one mention of him, I am confident he’s the right guy. His name was Elisha – the same name Robert gave to his own first son. The thing is – Robert was born in the early 1860s – which means his dad should have been the recently-arrived Patrick (O’)Moore.

The trail stopped at Elisha’s grandfather, a Civil War veteran born in Georgia near the turn of the previous century. Wherever our Moores came from, they came at least a half-century earlier than we thought they did. They moved to Oklahoma not to live with Cherokee relatives, but to an entirely different part of the state. From the family photos, I wondered if Wat had moved to the IT and married a native woman – but the marriage record says Ida was born in Arkansas. And Wat moved to the IT decades before that area was opened up to white settlers around 1890. Was he a “Sooner,” squatting on what should have been Indian lands?

So if that’s the case – who are all those very-not-white people in dad’s family pictures? And how did they get there..?

I took one of those commercial DNA tests and it found 0% native blood. But then I learned that as a female, my ancestry information came from my mom. My brother agreed to take the same test, and see what it told us about our Y chromosome.

0% native, and a small percentage of North African descent. Hmm… perhaps they were concealing a freedman, after all.

Tribal affiliations are cultural, not biological, and there is no known significant DNA difference between tribes that would allow DNA tests to identify a specific tribal ancestry. Even if there ever had been, the intermingling of forced relocation and generations of living in proximity would have erased it. So even if our DNA tests had shown native blood, there’d be no way to identify what tribe dad’s family might have been interacting with. Except…

It seems someone got it in their head to do some targeted testing on the Qualla – the Eastern Cherokee who never made the death march west. (They are also the community from whom “Patrick’s” wife was supposed to have come.) While they have still had generations to diverge, they are (arguably) among the least-changed tribes still in existence.

This genetic testing showed that the Qualla Cherokee were visibly different, genetically speaking, from other North American tribes. In fact, their DNA looked more like some North African peoples or Ashkenazi Jews than it did Native American. But that’s also – well, let’s call it “emerging research” – there are still a lot of very valid questions and concerns.

All of that is a little academic anyway – genetics don’t define tribal relationships. We had been hoping some of that information might lead us to the people in my dad’s family photographs, so that we could understand who they were, and who we might be to them. They were clearly a huge part of my grandfather’s early life – a grandfather who died before he could meet me, much less tell me about them himself.

I don’t know what all that means yet, and it will be interesting to see what I learn down the road. But I do know one thing: little of what my dad believed about his family history was accurate. Nothing about who he thought he was or where he thought his family came from was true.

Dealing with my dad’s death meant trying to find a way to resolve the unresolvable conflicts and hypocrisies that were so much a part of our relationship. That seems to be the case for many people. I found my resolution in these two stories.

The story of his family – of the things he thought he was, the things he thought he lacked – turned out to be a lie. A harmful one. It confused and misrepresented ties of identity with a tribe that has long been targeted for such claims, possibly in an effort to legitimize taking land that belong to natives (maybe not – there was clearly *some relationship there – but just as clearly, it was *not the relationship that they claimed). And it left my dad feeling “lacking” in so many ways – missing things he thought his family had once had, but which had, in reality, never existed.

The legend of the Tiger Balm Gardens – almost wholly absent of facts – contained the most important truths – the vision of the things he wanted to be, and to create for those he loved. It became, in its way, a roadmap.

And somewhere between the Legend and the Lie, was the man that he became.

My brusque, Viet Nam sailor of a dad collected fine, hand-painted porcelain teacups and saucers. I remember being so surprised when I discovered that collection, packed away in an attic while he remodeled part of his house.

When he wrote his will, he asked us kids to tell him what we wanted when he died. I answered: “one of your teacups.” They were a symbol to me of the unexpected depths of emotion in this outwardly-hardened man.

When the day came to execute his will, I looked through his cups and saucers for something that could be a constant reminder of the man he was, and the dreams he rarely articulated to others.

I chose this one.